Many UK drivers assume supermarket petrol stations are always cheaper than local or independent sites — but the reality is more nuanced.

Recent findings from the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) shed new light on how pricing, margins and competition differ between supermarket fuel stations and non-supermarket (often local) petrol stations. Understanding these differences can help drivers make better decisions at the pump.

Supermarket petrol stations are usually cheaper — but not always

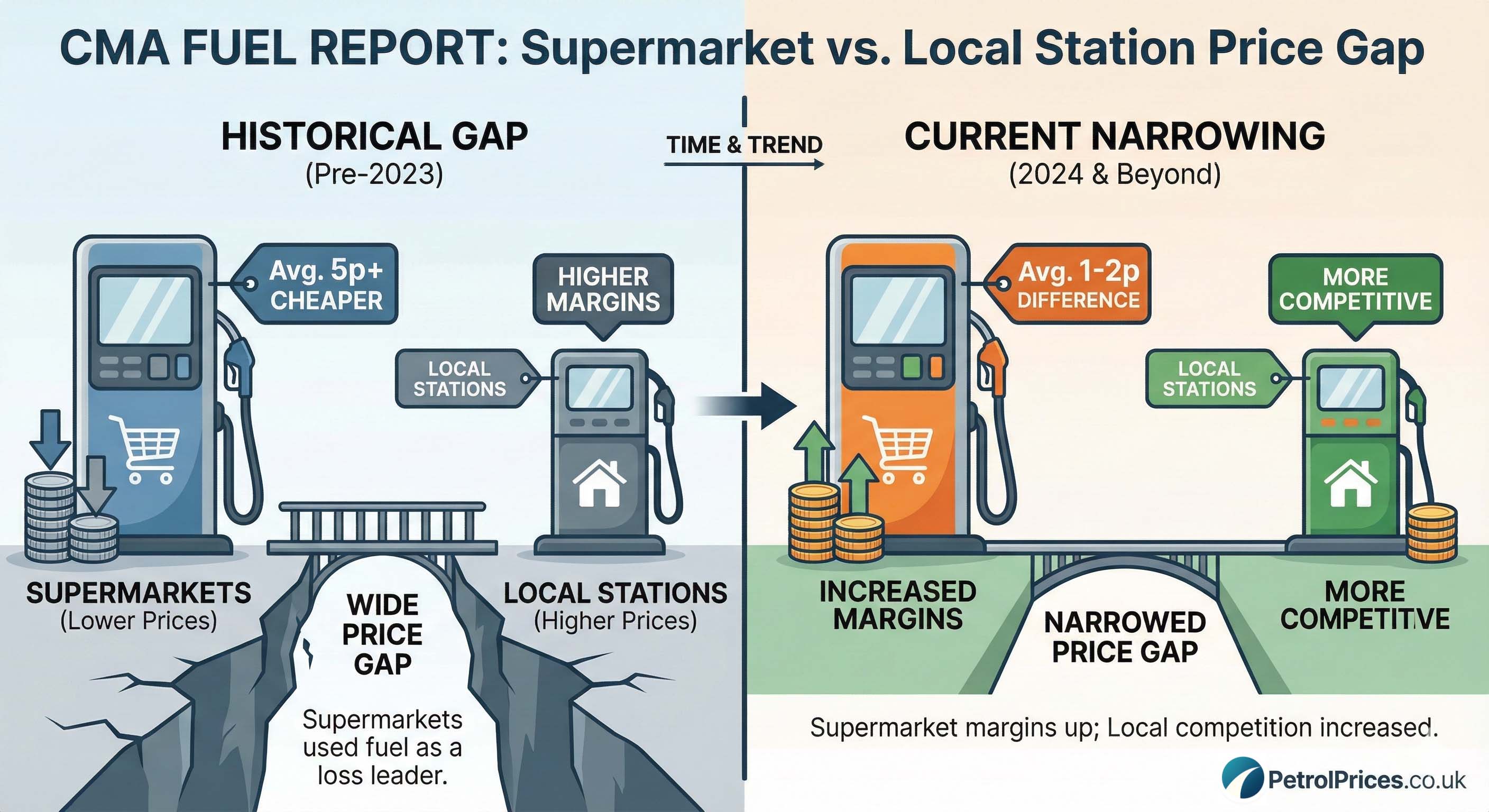

Supermarkets have long positioned fuel as a way to attract customers into their stores rather than as a major profit driver. As a result, their pump prices are often lower than those at nearby independent stations.

However, the CMA’s analysis shows that:

- Supermarkets still make a profit on fuel

- Their margins have increased compared with historic levels

- Prices don’t always fall quickly when wholesale costs drop

This means supermarket fuel isn’t guaranteed to be the best deal every time — especially if local competition is limited.

Local petrol stations tend to charge more — and here’s why

Non-supermarket petrol stations, which include independent sites and branded forecourts, typically operate under different conditions:

- Smaller volumes of fuel sold

- Fewer opportunities to offset costs with in-store retail

- Less buying power when sourcing fuel

- Higher exposure to local competition (or lack of it)

According to CMA monitoring, average margins at non-supermarket stations are significantly higher than those at supermarkets. This gap has remained persistent, particularly in areas where drivers have limited alternatives.

Competition matters more than brand

Key Finding

One of the most important findings is that local competition has a bigger impact on price than whether a station is a supermarket or independent.

Where several stations compete closely, prices tend to be lower and changes in wholesale costs are passed on more quickly. Conversely, where there are few nearby options, prices stay higher for longer and retailers face less pressure to reduce margins.

This explains why a supermarket station isn’t always the cheapest if it dominates a local area — and why some independents can be competitive when strong rivals are nearby.

Fuel margins are higher than drivers might expect

Retail margin is the difference between what a station pays for fuel and what drivers pay at the pump. The CMA found that:

- Both supermarket and non-supermarket margins remain above long-term averages

- Non-supermarket margins are consistently higher

- Elevated margins are not fully explained by operating costs

While supermarkets still tend to undercut independents, the data suggests neither group is passing on wholesale savings as quickly as drivers might expect.

Operating costs don’t fully explain the gap

Fuel retailers often cite rising costs such as wages, energy prices, security, and investment in EV infrastructure. These costs are real — but the CMA concluded they do not fully account for the size or persistence of higher margins, especially at non-supermarket sites.

This suggests pricing behaviour and competitive pressure play a bigger role than costs alone.

What this means when choosing where to fill up

For drivers, the takeaway is practical:

- Supermarkets are often cheaper, but not guaranteed to be

- Local stations may charge more, especially where competition is weak

- Prices can vary sharply even within short distances

Relying on assumptions rather than checking prices can lead to unnecessary overspending.

Why comparing prices beats loyalty

Brand loyalty or convenience can come at a cost. With price differences of several pence per litre common between nearby stations, regularly checking prices can save drivers a noticeable amount over the course of a year.

This is particularly important in areas dominated by one type of retailer, where price competition is limited and margins tend to stay higher.

The bigger picture

The CMA’s findings highlight that the fuel market doesn’t behave the same everywhere. Supermarkets and local petrol stations operate under different pressures, but both benefit when competition is weak. Until competition improves and price changes flow through more consistently, drivers who compare fuel prices — rather than relying on brand assumptions — are best placed to keep costs down.